Wabi-sabi is a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.

It is a beauty of things modest and humble.

It is a beauty of thing unconventional.

While sitting beneath the cherry blossoms at a typical Hanami (“flower viewing”) party in Japan it’s easy to forget that behind the alcohol-fueled revelry you’re actually taking place in a very particular form of appreciation centred on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. Nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.

Aesthetic ideals are central to Japan’s cultural identity and the Japanese language has all sorts of fancy words for describing our feelings towards how we perceive the world but underlying them all is the notion of wabi-sabi (侘寂).

As it relates to notions of beauty, it’s a concept that has been misunderstood and intentionally obscured throughout history, often by those peddling mystical knowledge or items claiming to imbue wabi-sabi qualities. The misconception here is that wabi-sabi is not an intrinsic property of things, but an “event”, or state of mind. In other words, the beauty of wabi-sabi “happens”, it does not reside in objects or environments directly.

The best text I’ve found on the subject is the short and concise book ‘Wabi-sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers‘ by Leonard Koren which breaks down the material and philosophical characteristics of wabi-sabi. Below I’ve attempted to paraphrase some of the key points in the hope that it might be of some interest to anyone looking for a little more colour than can be found on Wikipedia.

Definition

Wabi-sabi can in its fullest expression be a way of life. At the very least, it is a particular type of beauty.

The closest English word to wabi-sabi is probably “rustic” — simple, artless, or unsophisticated” — but, while it is often the initial impression many people have when they first see a wabi-sabi expression, this represents only a limited dimension of the wabi-sabi aesthetic. Wabi-sabi also shares some characteristics with “primitive art”, that is, objects that are earthy, simple, unpretentious, and fashioned out of natural materials.

The Japanese words “wabi” and “sabi” originally had quite different meanings which over the centuries blurred so much that today they can be used interchangeably (or together as in “wabi-sabi”) but if we look at them separately, we could characterise their differences as follows:

| wabi refers to | sabi refers to |

|---|---|

| a way of life, a spiritual path | material objects, art and literature |

| the inward, the subjective | the outward, the objective |

| a philosophical construct | an aesthetic ideal |

| spatial events (space) | temporal events (time) |

History

Wabi-sabi was conceived and developed amid a period of intense political and social upheaval in Japan during the Sengoku era (c. 1466 – 1598) and is sometimes compared to Europe’s Dark Ages.

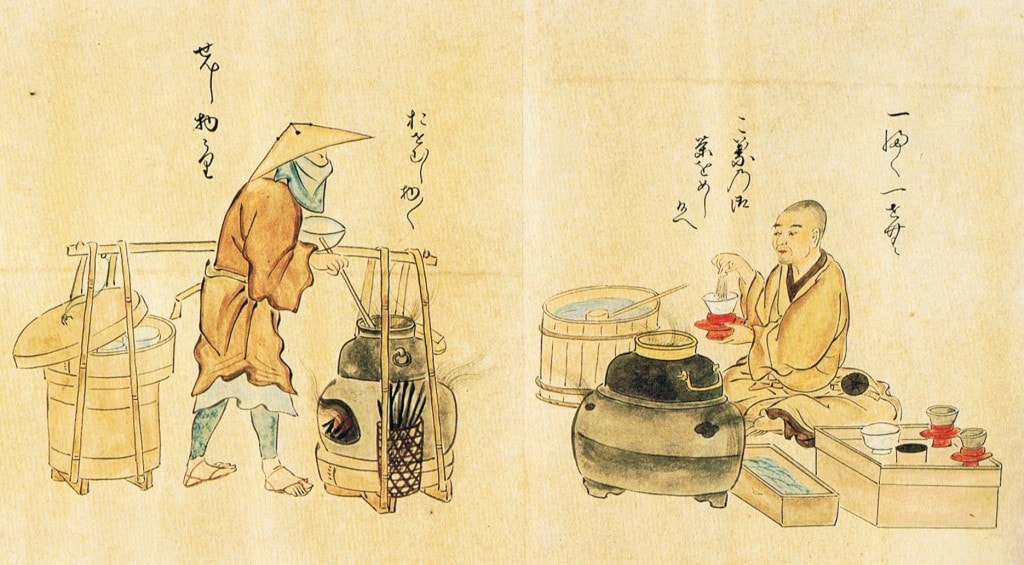

The locus of invention was the tea room where, insulated from the hardships and concerns of the outside world, artistic and philosophical values independent of conventional society took root. The leaders of this artistic adventure were the tea masters who prepared and presented tea during carefully designed ceremonies noted for their originality and unpredictability.

The most historically revered of all the tea masters was Sen no Rikyu (千利休):

Pre-Rikyu

The initial inspirations for wabi-sabi’s principles come from ideas about simplicity, naturalness, and acceptance of reality found in Taoism and Chinese Zen Buddhism. It also absorbed the ethereal ambience of Noh, a form Japanese musical performance, known as Yugen (profound grace and subtlety).

By the 16th-century the separate elements of wabi-sabi coalesced into a distinct aspect of sophisticated Japanese culture, reaching its zenith in the context of the tea ceremony (茶の湯). The tea ceremony became a social art form combining architecture, interior and garden design, flower arranging, painting, food preparation, and performance.

The first wabi-sabi tea master was Murata Shuko (村田珠光), a Zen monk from Nara, who intentionally used locally produced utensils instead of highly-decorated foreign ones.

Rikyu

Sen no Rikyu (1522 – 1591), the son of a merchant, brought wabi-sabi to its apotheosis in the late 16th-century by placing crude, anonymous, indigenous Japanese and Korean folk-craft on the same artistic level as slick Chinese treasures. In order to convey the meaning and significance of physical objects, environments and events, he created a new kind of tea room based on the form of a farmer’s hut made from rough mud walls, thatched roofs, and misshapen exposed wooden beams.

He consciously juxtapositioned the old with the new, smooth with rough, costly with expensive, complex with simple… For example, old chipped rice bowls might be lovingly repaired and repurposed as tea bowls. In other words, the imagery of genteel poverty was actively cultivated.

His wealthy employer didn’t appreciate his aesthetic ideals and ordered Rikyu to commit ritual suicide at the age of seventy.

Post-Rikyu

Like religious fundamentalists who claim their interpretation of doctrine to be “correct”, organised tea factions have been preoccupied with establishing their legitimacy based on the teachings of Rikyu since his death. In the process, personal judgement and imagination have been wrung out of the ceremony with even the most minute hand gestures being rigidly prescribed. This has led to institutionalised wabi-sabi becoming its opposite: slick, polished, and gorgeous — despite maintaining the consistency of the traditional forms.

Wabi-sabi is no longer the true ideological or spiritual heart of tea, even though things that sound and look like wabi-sabi are still trotted out by the tea orthodoxy.

Obfuscation

Although almost every Japanese person will claim to understand the feeling of wabi-sabi — it is, after all, supposed to be one of the core concepts of Japanese culture — very few can articulate this feeling.

Most Japanese never learned about wabi-sabi in intellectual terms since there are no books or teachers to learn about it from. This is not by accident. Throughout history a rational understanding of wabi-sabi has been intentionally thwarted by:

- Zen Buddhism – Wabi-sabi has been peripherally associated with Zen Buddhism as it exemplified many of Zen’s core spiritual-philosophical tenets. Essential knowledge, in Zen doctrine, can be transmitted only from mind to mind, not through written or spoken word. “Those who know don’t say; those who say don’t know“. As a consequence a clear definition has been studiously avoided.

- The iemoto system – Japanese cultural arts such as the tea ceremony, flower arranging, calligraphy, song and dance have traditionally been controlled by groups of family businesses headed up by a chief called the iemoto (家元). Information about “exotic” concepts like wabi-sabi is often artfully obscured as a means of marketing bait used to tantalise potential customers.

- Aesthetic obscurantism – a myth of inscrutability around wabi-sabi has been fostered because, according to some Japanese critics, ineffability is a part of its specialness. From this view point, missing of indefinable knowledge is simply another aspect of wabi-sabi’s “incompleteness”. To fully explain the concept might, in fact, diminish it.

The Wabi-Sabi Universe

Wabi-sabi can be called a “comprehensive” aesthetic system. Its world view, or universe, is self-referential. It provides an integrated approach to the ultimate nature of existence (metaphysics), sacred knowledge (spirituality), emotional well-being (state of mind), behaviour (morality), and the look and feel of things (materiality). The more systematic and clearly defined the components of an aesthetic system are, the more useful it is.

Metaphysical Basis

Things are either devolving toward, or evolving from, nothingness – e.g. a simple grass hut may be fashioned from a bed of rushes and while the hut will eventually disappear it will remain in the memory of the person who made it or those who are told of it. Wabi-sabi in its purest form is precisely about these delicate traces at the borders of nothingness. Instead of being empty space, as in the West — nothingness is alive with possibilities.

Spiritual Values

- Truth comes from the observation of nature –

- All things are impermanent – the planets and stars, and even intangible things like family heritage, historical memory, scientific theorems, great art and literature all eventually fade into oblivion and nonexistence.

- All things are imperfect – even the sharp edge of a razor blade, when magnified reveals microscopic pits and chips. As things begin to break down they become even less perfect and more irregular.

- All things are incomplete – including the universe itself, and in a constant state of becoming or dissolving. The notion of completion has no basis in wabi-sabi.

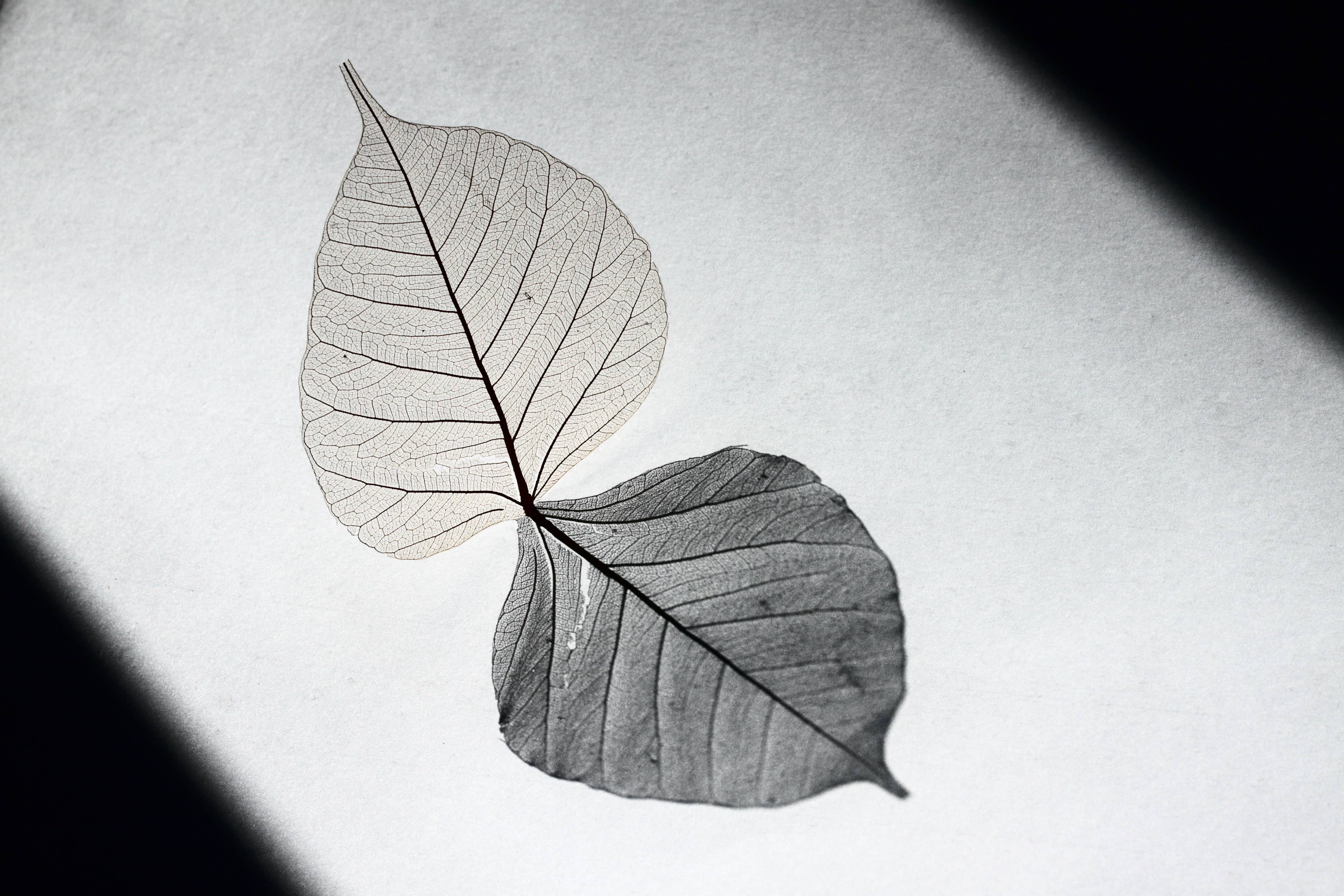

- “Greatness” exists in the inconspicuous and overlooked details – unlike the Western ideal of beauty as something monumental, spectacular, and enduring, wabi-sabi is not found at moment of bloom and lushness, but in moments of inception or subsiding. It is about the minor and the hidden, the tentative and the ephemeral: things so subtle and evanescent they are invisible to vulgar eyes. To experience wabi-sabi you need to slow down, be patient, and look very closely.

- Beauty can be coaxed out of ugliness – wabi-sabi suggests that beauty is a dynamic event that occurs between you and something else. It can occur at any moment given the proper circumstances, context, or point of view. While a farmer’s hut is a lowly environment, in the proper context and with guidance, it can take on exceptional beauty.

State of Mind

- Acceptance of the inevitable – as with the ruins of a splendid mansion, crumbled and overgrown with weeds, wabi-sabi forces us to contemplate our own mortality. This is mingled with the bittersweet comfort that all existence shares the same fate. This may be evoked through poetry or common sounds which suggest the sad-but-beautiful feelings of wabi-sabi. E.g. the mournful caws of crows or the forlorn bellowing of foghorns.

- Appreciation of the cosmic order – in the same way that medieval European cathedrals were constructed to emotionally elicit transcendent feeling, the way rice paper transmits light in a diffuse glow, or the manner in which clay cracks as it dries, all represent the physical forces and deep structures that underlie our everyday world.

All around, no flowers in bloom

Poem by Fujiwara no Teika (藤原定家)

Nor maple leaves in glare,

A solitary fisherman’s hut alone

On the twilight shore

Of this autumn eve.

Moral Precepts

- Get rid of all that is unnecessary – wabi-sabi means treading lightly on the planet and knowing how the appreciate whatever is encountered, no matter how seemingly insignificant. It tells us to stop our preoccupation with success — wealth, status, power, and luxury — and enjoy the unencumbered life. This involves some tough decisions and acknowledging that it is just as important to know when to make choices, and when not to make choices: to let things be. We still live in a world of things and have to find a delicate balance between the pleasure we get from them and the pleasure we get from freedom from things.

- Focus on the intrinsic and ignore material hierarchy – the symbolic act of either bending or crawling to enter a tea room through a purposely low and small entrance invokes humility in an egalitarian atmosphere. Hierarchical thinking — “this is higher/better, that is lower/worse” — is not acceptable. Everyone is equal. Similarly, the objects inside a tea room are not valued based on their maker or cost — mud, paper, and bamboo have more intrinsic wabi-sabi qualities than gold, silver, and diamonds. An object obtains the state of wabi-sabi only for the moment it is appreciated as such.

Material Qualities

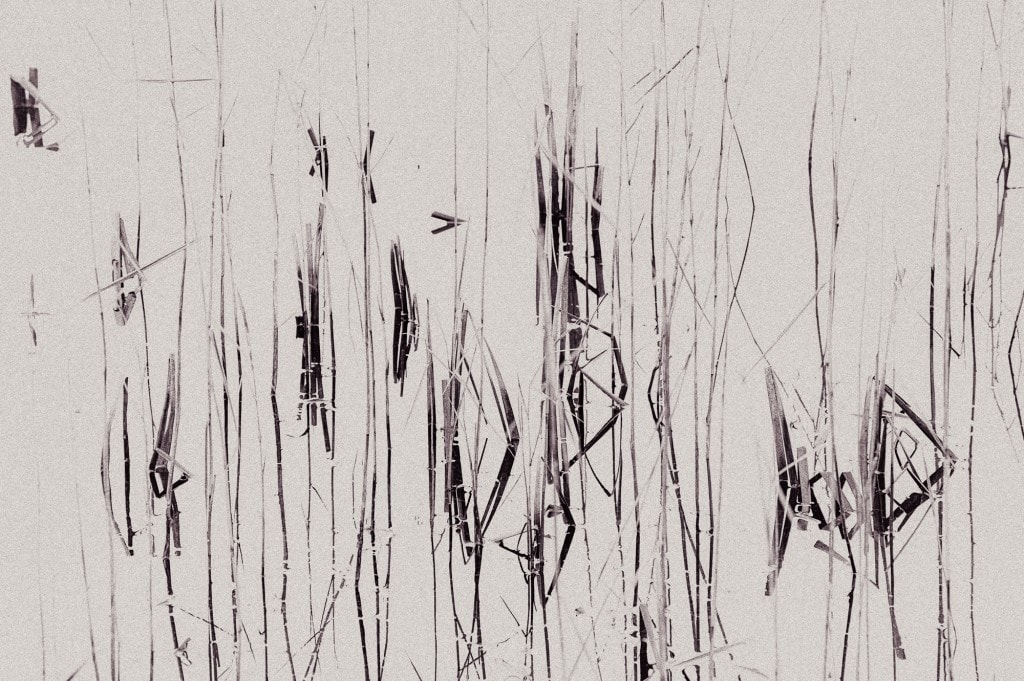

- The suggestion of natural process – things wabi-sabi are expressions of time frozen. They are made of materials that are visibly vulnerable to the effects of weathering and human treatment. They record the sun, wind, rain, heat, and cold in a language of discolouration, rust, tarnish, stain, warping, shrinking, shrivelling, and cracking. Though things wabi-sabi may be on the point of dematerialisation (or materialisation) — extremely faint, fragile, or desiccated — they still possess an undiminished poise and strength of character.

- Irregular – things wabi-sabi are indifferent to conventional good taste. As a result, things wabi-sabi often appear odd, misshapen, awkward, or what many people would consider ugly (e.g. a broken bowl glued back together).

- Intimate – things wabi-sabi are usually small and compact, quiet and inward-orientated. They beckon: get close, touch, relate. Places wabi-sabi are small, secluded, and private environments than enhance one’s capacity for metaphysical musings. Tea houses often have low ceilings, small windows, tiny entrances, and very subdued lighting. They are tranquil and calming, enveloping and womb-like. They are a world apart: nowhere, anywhere, everywhere. Every single object within seems to expand in importance in inverse proportion to its actual size.

- Unpretentious – things wabi-sabi are unstudied and inevitable looking. They do demand to be the centre of attention. They are understated and unassuming, yet now without presence or quiet authority. Things wabi-sabi coexist with the rest of their environment and are only appreciated during direct contact and use. They have no need for provenance — it is best if the creator is of no distinction, invisible, or anonymous.

- Earthy – things wabi-sabi can appear coarse and unrefined. They are usually made from materials not far removed from their original condition and are rich in raw texture and rough tactile sensation. Their craftsmanship may be impossible to discern.

- Murky – things wabi-sabi have a vague, blurry, or attenuated quality — as things do as they approach nothingness (or come out of it). Things wabi-sabi come in an infinite spectrum of grays, browns, muted greens and off-whites.

- Simple – simplicity is at the core of all things wabi-sabi. Nothingness is the ultimate simplicity but the before and after are not so simple. To paraphrase Rikyu, the essence of wabi-sabi, as expressed in tea, is simplicity itself: fresh water, gather firewood, boil the water, prepare tea, and serve it to others. Further details are left to one’s own invention but one must exercise restraint and avoid crossing over into ostentatious austerity.Things wabi-sabi are emotionally warm, never cold. This is achieved by:

- Paring down to the essence, but without removing the poetry

- Keeping things clean and unencumbered, but not sterilised

- Keeping conspicuous features to a minimum

- Using a limited palette of materials

Comparison with Modernism

“Modernism” is another complex term that cuts a wide path across art and design history, attitudes, and philosophy but can serve as a useful benchmark in 20th-century industrialised society against which to compare what wabi-sabi is and isn’t (think about the type of pieces you see in the MoMA).

Similarities

- Both apply to all manner of man made objects, spaces and designs

- Both are strong reactions against the dominant, established sensibilities of their time (modernism from 19th-century classicism, wabi-sabi from 16th-century Chinese perfectionism)

- Both have readily identifiable surface characteristics (modernism is seamless, polished and smooth, wabi-sabi is earthly, imperfect, and variegated)

- Both eschew any decoration that is not integral to structure

- Both are abstract, non representational ideals of beauty

Differences

| modernism | wabi-sabi |

|---|---|

| Expressed in the public domain | Expressed in the private domain |

| Mass-produced/modular | One-of-a-kind/variable |

| Expresses faith in progress | There is no progress |

| Future-orientated | Present-orientated |

| Geometric form (sharp, precise, definite shapes and edges) | Organic form (soft, vague shapes and edges) |

| Manmade materials | Natural materials |

| Ostensibly slick | Ostensibly crude |

| Needs to be well-maintained | Accommodates to degradation and attrition |

| Generally light and bright | Generally dark and dim |

| Function and utility are primary values | Function and utility are not so important |

| Everlasting | To everything there is a season |

Beauty at the edge of nothingness

Wabi-sabi is the antithesis of the Classical Western idea of beauty as something perfect, enduring, and monumental. In other words, wabi-sabi is the exact opposite of what slick, seamless, massively marketed objects, like the latest iPhone, aesthetically represent.

We often tacitly define beauty as perfection objectified. But somewhere buried in our psyches is the realisation that being human fundamentally implies being imperfect. So when someone suggests that imperfection may be just as beautiful—just as valuable—as perfection, it is a welcome acknowledgement.

Further Reading

- Wabi-sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers — Leonard Koren

- Wabi-sabi: Further Thoughts — Leonard Koren

- In Praise of Shadows — Junichiro Tanizaki

- The Book of Tea — Kakuzo Okakura

- Koyaanisqatsi — Godfrey Reggio

Reply