In Japan, I often find myself lost for words at the beautiful integration of the natural landscape with manmade architecture (be it traditional or modern). It seems to be hardwired into the cultural DNA of the country, right down to the religious worship of nature embodied in Shintoism.

At the beginning of the year, I had the pleasure of visiting the Odawara Art Foundation’s Enoura Observatory (江之浦測候所) which has recently opened in a sleepy district on the eastern coast overlooking Sagami Bay, about an hour from Tokyo.

It is the creation of photographer and architect Hiroshi Sugimoto, who became famous for his black-and-white images of abandoned theatres and seascapes.

As if guided by an unseen hand, I was drawn to this place of memories. In a sprawling mikan citrus grove in Enoura, I established the Odawara Art Foundation with the aim of conveying the essence of Japanese culture to a wider audience.

The Japanese people developed a unique culture incorporating the worship of myriad deities and spirits of the natural realm. In today’s grim world of rampant materialism and consumerism, when so much of this natural splendour has been destroyed, it is the revival of these ancient Japanese traditions that we need most.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Sugimoto established the Odawara Art Foundation in order to host other artists for exhibitions and performances that “assist in the reconsideration of history” and to that end, Enoura Observatory includes exhibition spaces, a teahouse and two Noh (classical theatre) stages.

As well as this, the grounds are home to monolithic stone artefacts Sugimoto has collected over his life and spectacular structures he designed to frame the landscape as well as “still look nice after civilization is gone”.

Below is a non-exhaustive photographic trip through the site but I highly recommend taking a trip there yourself if you are in Japan, they really don’t do the place justice.

Paving stones used throughout the complex originate from the Kyoto tramway. Having been used for decades as roads, their surfaces are worn, creating unique textures. Launched in 1895, the Kyoto tram was the first of its kind in Japan. The tram stopped operating in 1978.

The one hundred-meter-long gallery sits one hundred meters above sea level and has a cantilevered roof. One side is supported by a stone wall covered in speckled Oya stone while the opposing wall is made of glass windows with no supports.

Some of Sugimoto’s seascape photos are currently being exhibited.

Paving stones from the old Kyoto tramway are arranged around a central stone which was once the base of a pillar at a temple. Larger rocks at the rim were originally quarried for the walls of Edo Castle.

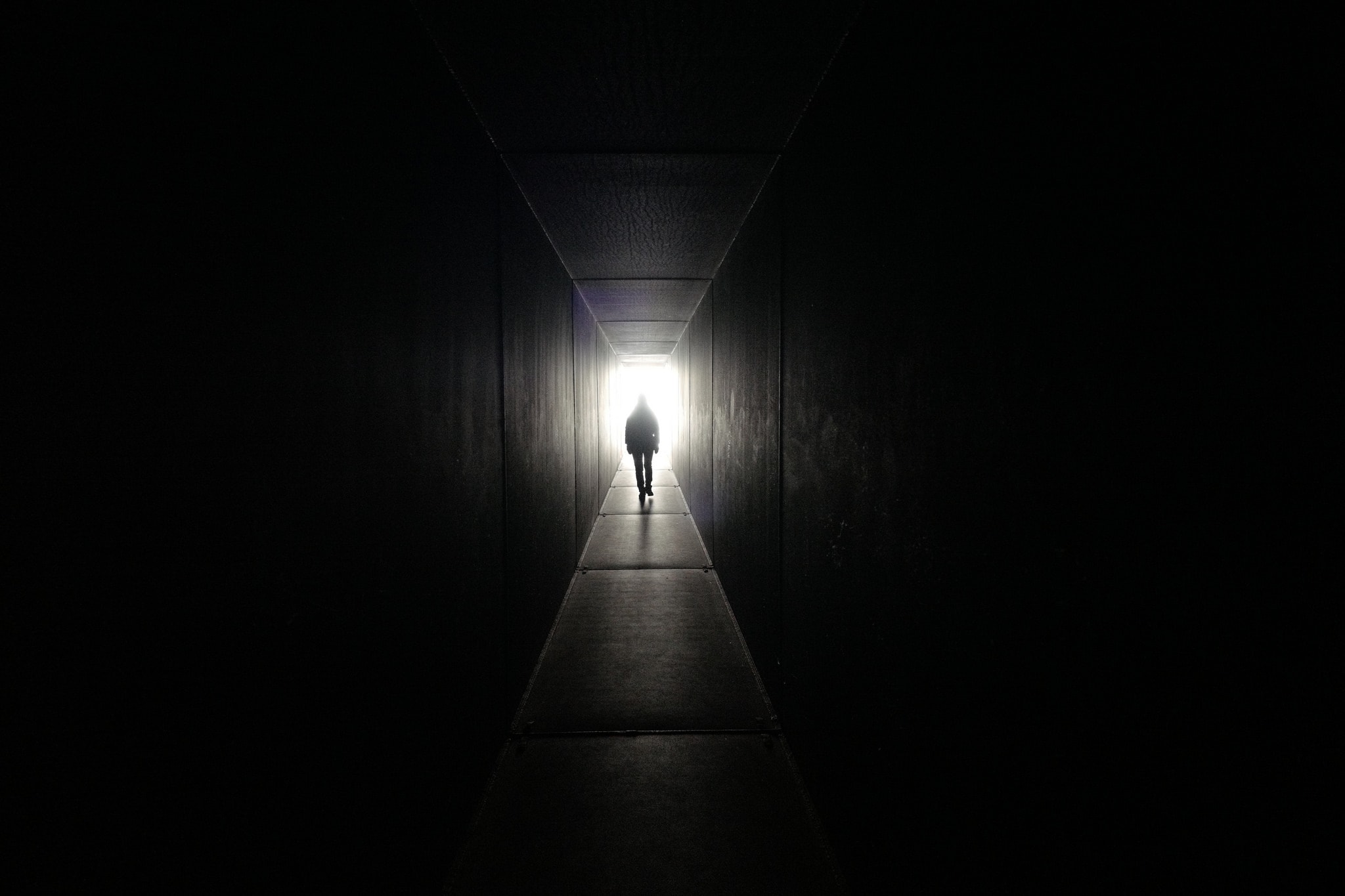

A human-sized tunnel is formed from plate steel beneath the gallery, aligned so that on the morning of the winter solstice, the sun rises from Sagami Bay, sending its light through the 70-meter aperture to illuminate the large stones at the other end.

Ancient cultures around the world celebrated the winter solstice as a turning point in the cycle of death and rebirth. Developing an awareness of how the sun rises and the season’s change was one trigger for humankind’s acquiring of consciousness.

Walking through the tunnel towards the light, you reach a perfectly framed landscape of the sea meeting the sky, mirroring Sugimoto’s own work.

The translucent glass stage sits on a kakezukuri framework of Hinoki cypress parallel to the tunnel. The auditorium is a full-size recreation of a ruined Roman amphitheatre in Italy. To the audience, the stage appears to be floating on the sea.

The design of the stone stage is based on the dimensions of a Noh stage. It was conceived for Noh plays to start just before dawn when the night is giving way to daylight and for the actors to return to the underworld as the sun rises directly behind the stage.

A 23-ton slab of rock has been used for the bridge leading to the stage. A wide crack runs its length.

This heap of stones is reminiscent of the stone chambers found in burial mounds. Its tip points towards to sun at midday on the spring and summer equinoxes.

The gate in front of a tea house was assembled to resemble a pre-medieval stone gate in Odachi, Yamagata prefecture. An old stone sarcophagus lid is used as the stepping stone directly under the gate.

The Uchoten tea house is a reinterpretation of the Taian tea house, through to have been designed by Sen no Rikyu. Taian is regarded as the perfect expression of the simple, modest type of tea ceremony favoured by Rikyu. He deliberately recreated the sacred “simplicity” of seclusion deep within the mountains.

When it rains, you can hear the raindrops drumming on the corrugated iron roof, hence the tea house’s name of U-cho-ten “rain-listen-heaven”.

Light comes through the exposed wattle windows into a tiny two-tatami-mat room to create an extraordinary space out of the shadows. Commonly available wood was used, rather than anything rare and precious, while the walls are made of cheap mud plaster.

The block of optical glass in front of the crawl door glows when it catches the sunlight on its cut edges.

The Meigetsu gate was originally constructed for a temple in Kamakura during the Muromachi period. Its storied history saw it dismantled and moved multiple times, with its last home being the front gate to the Nezu museum before the museum itself was rebuilt and the gate donated to the foundation.

The walls on either side of the gate are made from rows of bamboo sliced in half lengthways to resemble clumps of rushes or tokusa in Japanese.

In order to visit Enoura Observatory, tickets need to be booked online in advance. Only a limited number of guests are admitted each day and visits are restricted to two-hour slots. It’s not nearly enough time to fully appreciate this sublime exploration of the past, present and future.

Reply