The weeks (and sometimes months) of our lives on Shikoku, left an indelible impression on us all. But the walk is a solitary endeavour. What did we learn collectively? And how can these learnings help future Henro, the residents of Shikoku, and Henro Alumni everywhere?

In June, we conducted a survey to learn more about people’s motives and experiences as henro.

From our data, the respondents fell into a few broad categories:

- Young life changers – aged 20 to 35. Sought time in nature and optimised for a tight budget.

- Older adventurers – aged 50+. Valued cultural connection, physical challenge, and dependable lodging.

- Spiritual seekers – aged 30+. Came to experience, or explore Buddhism. Ascetic budget and lodging choices.

Together, these pilgrims primary motivations for walking the pilgrimage were:

- Physical challenge

- Taking time out to think

- Enjoying nature

While some stated an interest in the spiritual side of the pilgrimage, this was not the main motivation for most.

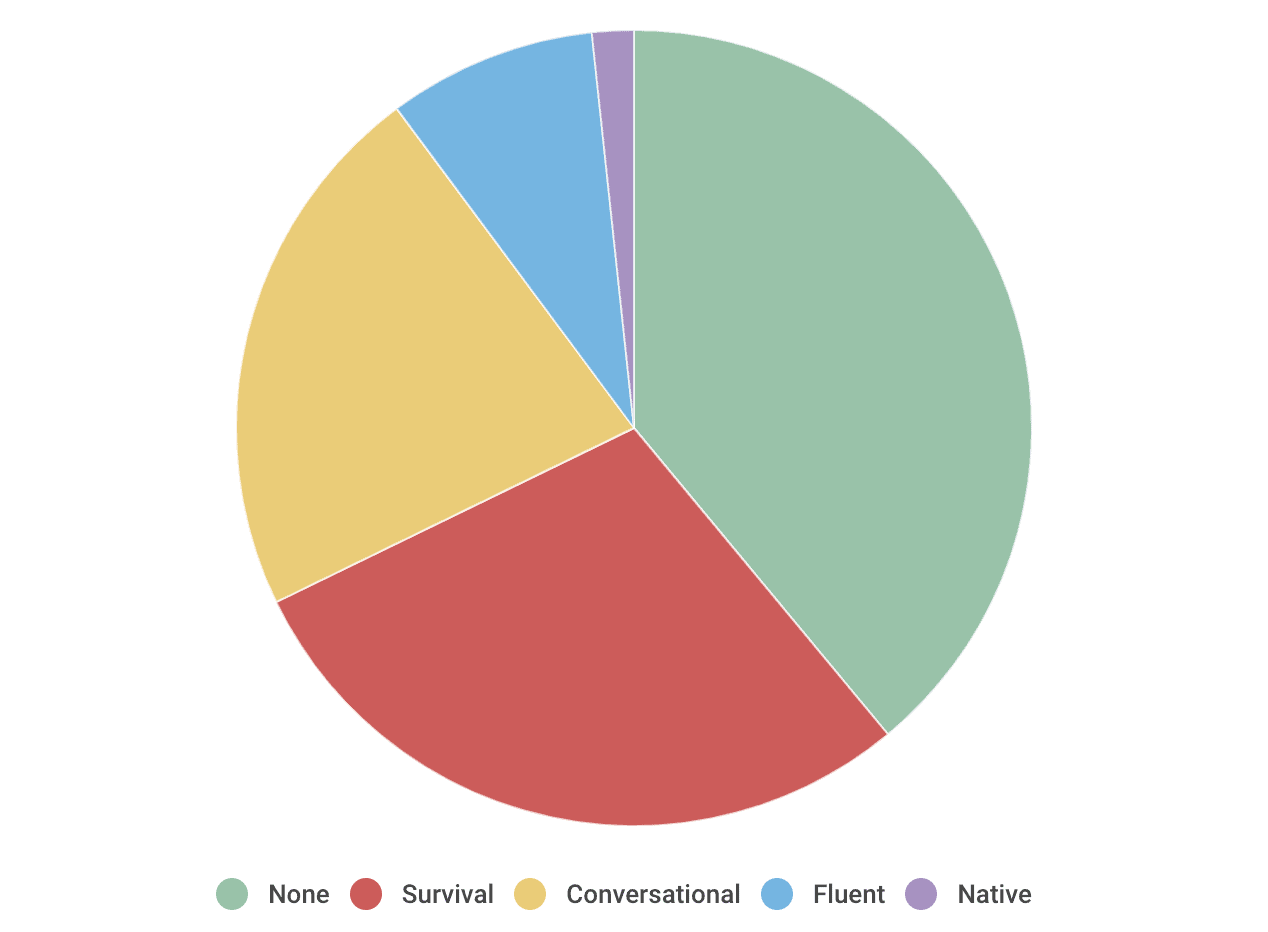

Unsurprisingly, communication was a big hurdle for pilgrims, with almost 2/3rds of Henro unable to converse in Japanese. This affected lodging most directly, as many were uncomfortable with both the reception foreign Henro received and also their inability to change the dynamic. However, most also cited the hardships and unpredictability of the pilgrimage as important to their experiences.

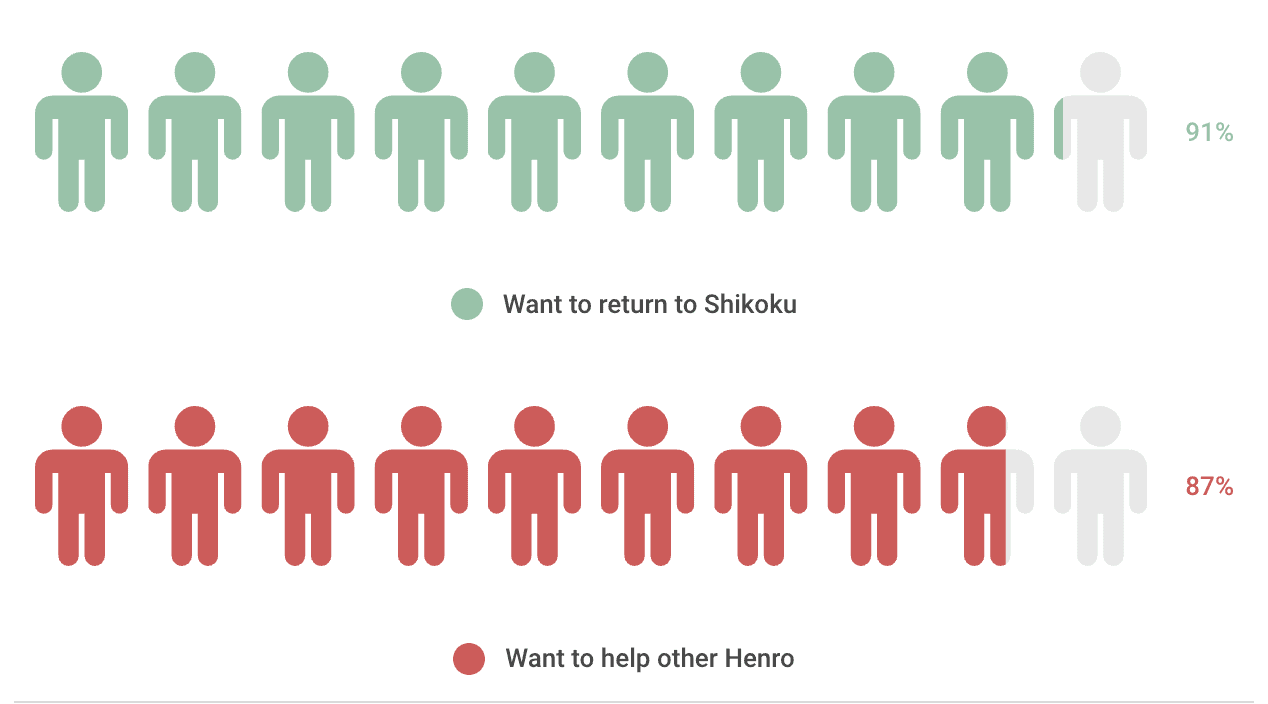

The Maeyama Ohenro Kōryū Salon (前山おへんろ交流サロン) recorded 200 non-Japanese Henro in 2016, a number which has been almost doubling annually. Only a fraction of these Henro are connected via Facebook groups (Ohenro San being the largest at ~600 members) and message boards. Almost all (91%) of Henro want to return to Shikoku and 87% of the respondents wanted to actively help future Henro.

If you’re interested in helping out, and you haven’t yet completed the survey, we would still love to hear from you. Thank you to all who participated to date!

What we learned

Demographics

The 46 respondents ranged from 22 to 66 years old and came from 15 nationalities (mainly in America and Europe).

40% of people found the pilgrimage by word-of-mouth, with another 30% discovering it through books and documentaries. Online diaries/blogs also played an important role in giving people a flavour of the pilgrimage as well as helping future Henro plan their trip. 76% of people bought the English map book.

Time and costs

Excluding outliers, on average people spent 45 days in Shikoku (6.5 weeks) and took 4 rest days during their walk (every 11 days). 42% of people spent ¥100-300,000 yen, excluding transport, with those who stayed a minshuku/hotels leaning towards ¥300-600,000 yen. Based on this we’d recommended that Henro who want stay in formal accommodation each night budget JPY ¥10,000 per day.

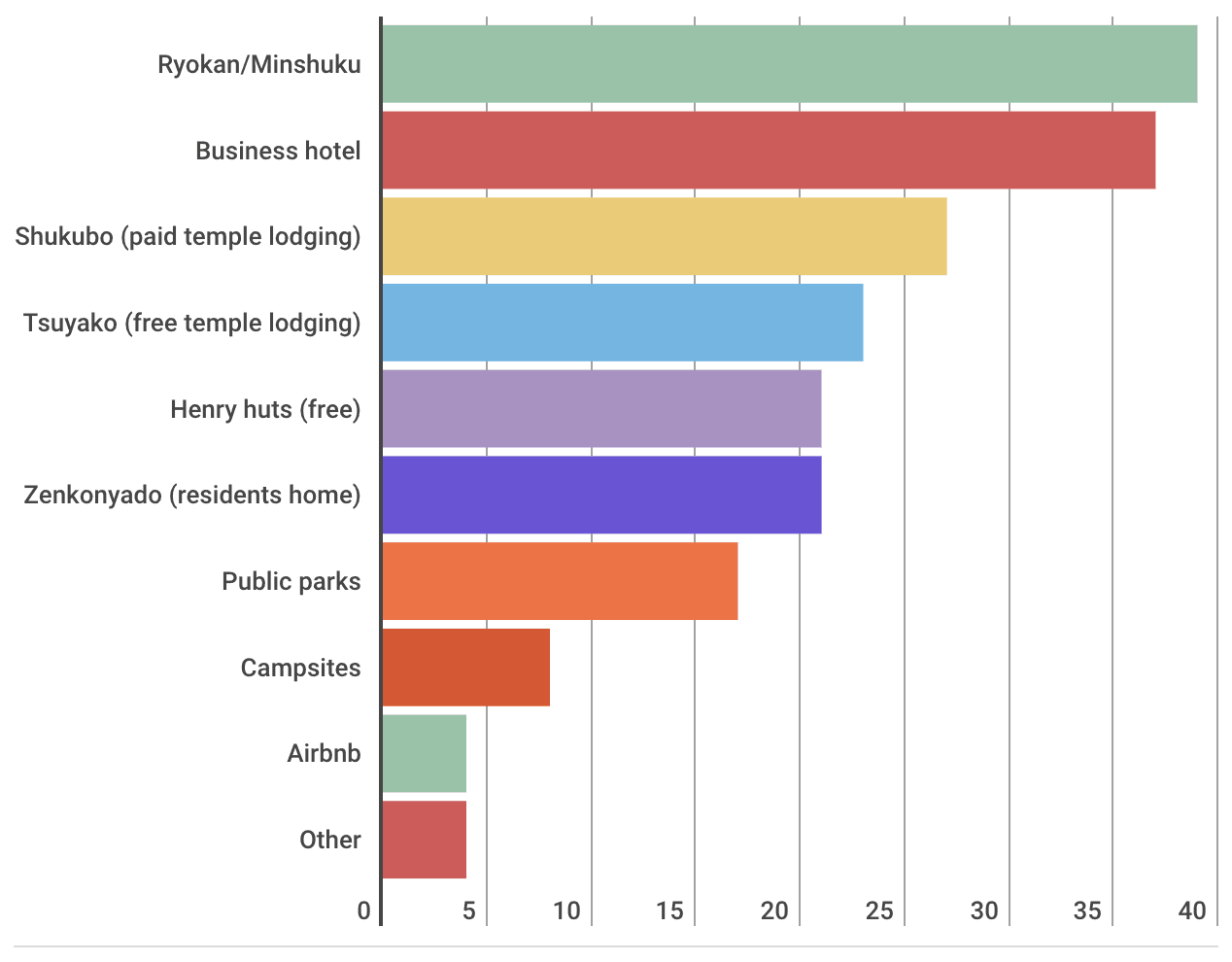

Where do Henro sleep?

Minshuku/ryokan and business hotels were the most frequently used type of lodging with 80% of pilgrims having stayed at them. Half of all surveyed had used some form of free accommodation: at temples (tsuyado) and in residents homes (zenyonkado). Around 40% of people had camped at some point on their journey, with henro huts and public parks being popular places to stay overnight.

Interestingly, Airbnb has not taken off in Shikoku yet, with only a smattering of places available in the larger cities. Given the amount of seemingly vacant property on the island there definitely seems to be scope for entrepreneurial residents to take advantage.

Language

When it came to the language barrier, 27% of people described their Japanese level as “conversational”, 38% as “survival level” and 24% as “none”. While many people described the challenge as being part of the experience, it did cause some problems, especially for booking accommodation since few places offer online booking.

“There was a lot with smiles, the translation app on the iphone and silence. I felt sorry I couldn’t make conversation with the utterly friendly people. One time it gave us stress because we had to get some transport to the minshuku for we missed trains.”

“I would have liked to be able to converse more, but my language level was not a barrier.”

“I consider problems as part of the experience as pilgrim :-)”

Of those who speak some Japanese, two-thirds called by phone to book their accommodation. Those who don’t, relied on their previous night’s host to call ahead, communicating their intent through body language.

Some people came up with creative solutions to the problem although translation apps got mixed reviews due to the need for internet and their cumbersome controls. These sorts of interactions often caused some discomfort and occasionally led to misunderstandings.

“I think some people felt uncomfortable having us stay at their place because they felt uncomfortable with people who could not speak the language.”

“I had a picture dictionary with me which turned out to be extremely helpful showing people a cow and No, or bus and question mark!”

“I traveled with an American friend who speaks enough Japanese to get us by. Without her I would have been lost!”

Defining memories

Overwhelmingly pilgrims spoke of the kindness that local residents showed them as being the best memories of their time of the pilgrimage. Be it offerings of something to eat in an area with few restaurants or shelter during a storm, time and again these small (and sometimes large) gestures seemed to occur just at the right time.

“On my last night, I was trapped in the rain and asked a temple if I could setup a bivy under their deck, but they took me in and fed me and gave me a place to sleep.”

The pilgrimage challenges everyone, especially foreign visitors, to step outside their comfort zone in multiple respects; language, food or just the physical challenge required. Many talked about the satisfaction of overcoming these things and gaining new confidence in the strength they didn’t know they had.

“Going beyond my own physical borders and outside of my comfort zone by walking further than i thought i would make it. And then being rewarded by such a nice company and a lovely rest hut.”

Ascending to the mountain temples at Shōsan-ji (12) and Unpen-ji (66) were both mentioned as defining moments where hard ascents were rewarded by spectacular views and peaceful surroundings.

“Sleeping at Unpen-ji all alone in the tsuyado. In March this year: still some snow. So quiet and inspiring.”

Another theme that emerged was of the space between temples being an important time for self-reflection and sometimes loneliness.

“The ocean being near almost all the time, getting to know Buddhism turned out to be my life changer, osettai and gentleness of Shikoku people”

“Mentally the being alone was not something I could research.”

“Having the time and space to realize where I am in life, in my favorite country. It was amazing.”

“The crucial part is BETWEEN the temples.”

Hardships

The hardest aspects of the pilgrimage tended to be practical in nature. Busy roads, dangerous tunnels and blisters were common complaints with many saying they had underestimated just how much time walking along roads would be required.

“Roadwalking is punishing on the feet and it’s 80% at least of the trip.”

“Uphill stretches were all difficult for me! So many stairs, too! When I got home we discovered I had a stress fracture in one foot…”

With all the kilometres adding up each day, people soon realised that every ounce counts when it comes to packing. Some resorted to posting things back home.

“I soon realized how maniacally I should’ve reduced weight in my bag.”

“You need way less stuff than you think.”

Henro walking in June had to contend with torrential rain which when ongoing for multiple days could be really debilitating. Those daring to walk at the height of summer (July – August) had to endure temperatures during the day which regularly exceeded 35°C and ran the risk of heatstroke/dehydration.

“Walking in summer is really really tough.”

Another source of stress was finding accommodation, especially at the height of the spring season when lodgings get booked up quickly. Anecdotally, some Henro believed that some owners were reluctant to accept foreign guests due to previous bad experiences.

“Booking places to stay could be quite tiring, foreigners don’t have the best reputations.”

“Finding accommodations was sometimes stressful. We were mostly walking and therefore we had little flexibility as to where we wanted to stay.”

Snake, spider, and insect bites can cause anxiety and, in extreme cases, lead to a trip to the hospital. Few of these cases could have been avoided, but it’s always worth staying aware of your surroundings to avoid an unwanted encounter.

“I got bitten on the face by a spider or something when I was in a tsuyado and my face swelled up severely.”

What you wish you’d known

For many people, approaching the pilgrimage with an open mind and letting the details work themselves out day by day was an unanticipated joy that led to many serendipitous moments.

“It was good I did not know everything.”

“Being unprepared is part of the experience as pilgrim.”

For those interested in Buddhism, despite visiting the 88 temples, there was a scarcity of accessible information about the rituals and their meaning. This is disappointing, given the tensions this can cause when temples perceive foreigners as being uncouth.

“I would like to know more about what I would see at the temples/what to do there beyond what’s in the English guide book (e.g. more info on Shingon Buddhism).”

Completing the pilgrimage after facing weeks of ups and downs is unlike anything else, and that moment can often come with pangs of melancholia, the knowledge that it’s all over.

“How precious and short the walk in fact feels when you finish.”

Almost universally, pilgrims left with an amazing impression of Japan and its people.

“How awesome Japan is and how wonderful the people are.”

❤️

Reply