Having stayed overnight in a brand new hotel in the middle of an eerily empty business park near Hongqiao Railway Station, we woke at 4.30 am and took a high-speed train southwest from Shanghai.

The view from the train window showed the devastation wreaked on the countryside by China’s unprecedented industrial complex which has consumed fields and entire mountains across the nation.

After about 4.5 hours we emerged from the fog of development in Huangshan (黄山), where we switched to a taxi which drove us 40 minutes further to Huizhou Ancient City (徽州古城) in Anhui province. We had travelled there the week before Chinese New Year in order to visit some of the well-preserved villages from the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368 – 1911) in the surrounding area.

The proprietor of the guesthouse we were staying at met us outside the imposing city walls and guided us inside, passing beneath Xu Guo Stone Arch (許國石牌坊). Built in 1584, in honour of the vice-premier of the time, it has 8 columns made of stone with 12 lions standing at the base in various poses.

We were staying at September Hui zhou Homestay within a traditional building which was once a bathhouse. From the third floor, we had a marvellous view out over the rooftops of the old city. The clusters of grey-tiled and white-walled houses are typical of Hui-style architecture.

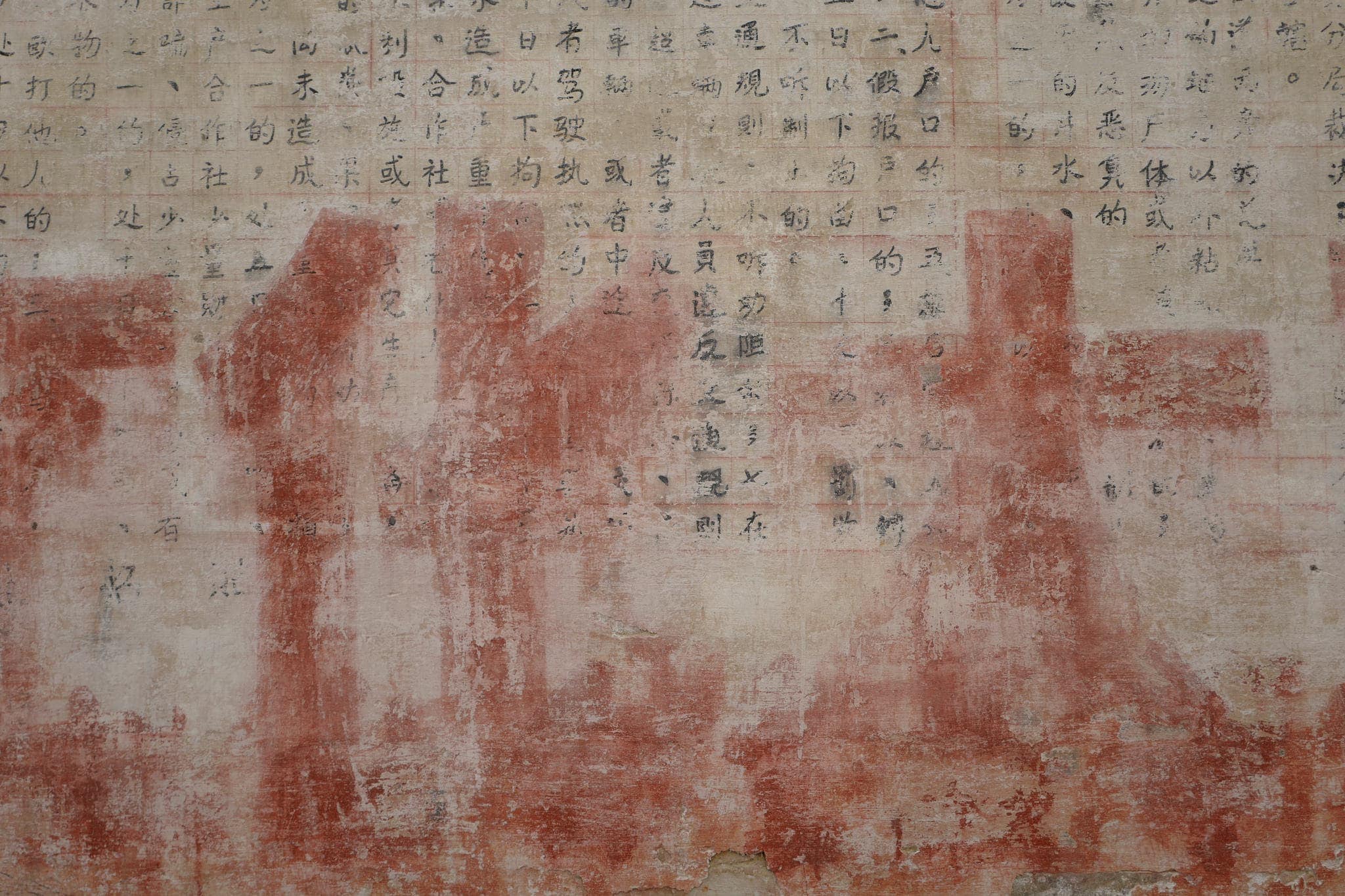

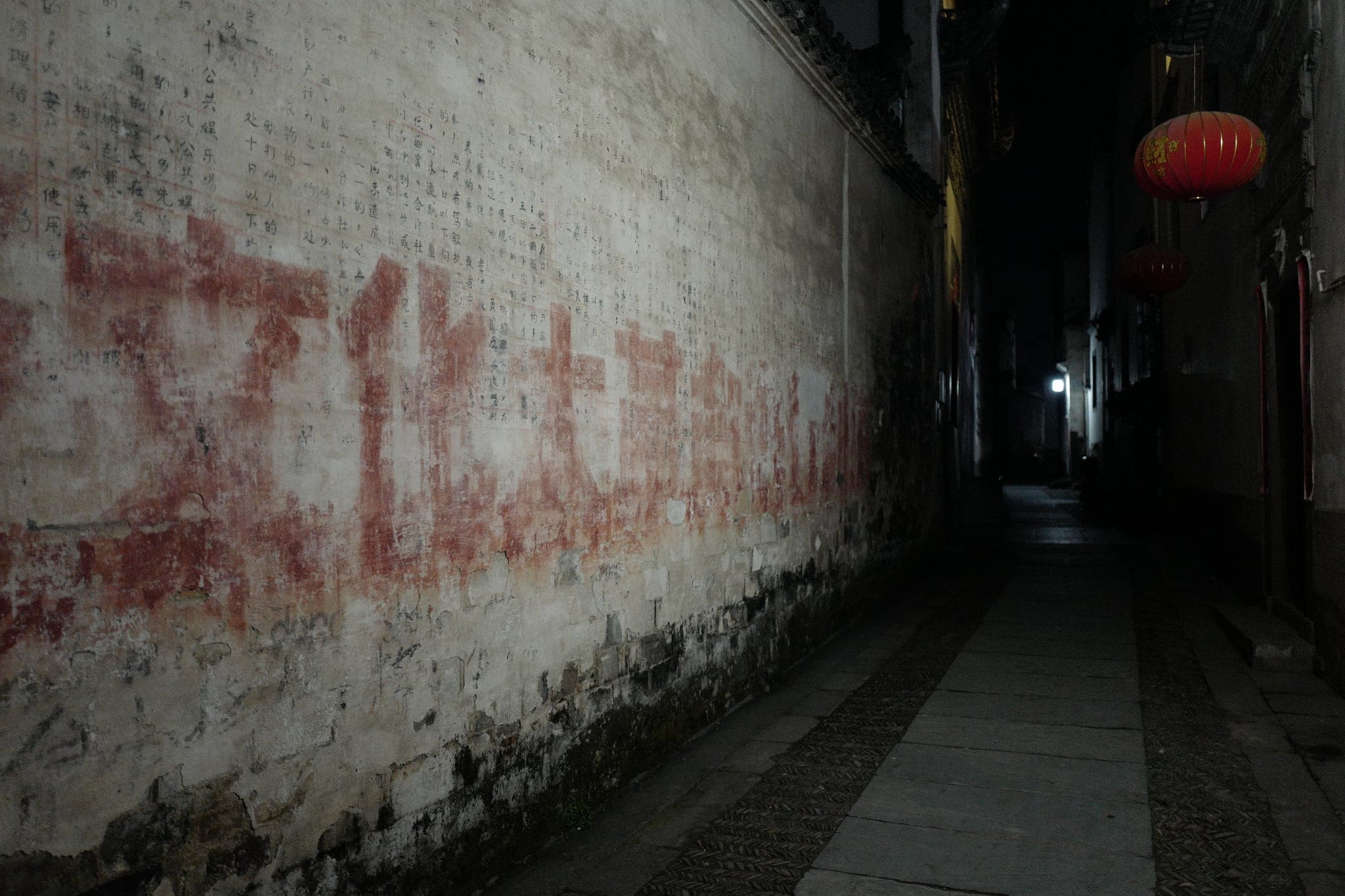

After getting settled in, we went for a walk around the city. The main street is full of modern shops selling knock-off clothing, but once you step away from the hustle and bustle you can quickly find yourself in cobblestone-paved alleys which were once home to the old merchants that built Huizhou.

While Anhui is today considered one of the poorer provinces in China, it was from here that some of the most successful merchants of the dynastic era originated. They dominated in everyday commodities such as salt, tea and lumber.

Wandering upwards, we arrived at a school sitting on a hill near the centre of the city. As well as a great view, we saw smallholdings squeezed into terraces on either side of the path. A loud bark from an angry-sounding dog made us retreat from venturing any further.

Back down on the other side of the city, we walked along winding Dounshan Street (斗山街) and were able to step inside some of the ancient villas. Most include interior courtyards open to the elements from above, held up by large wooden pillars. Lattice windows face inwards rather than out onto the lanes since the rich merchants of the time did not want people catching glimpses of their wealth or wives, concubines and daughters.

While some of the villas are still occupied, many are in a poor state of repair and their interiors have collapsed. The complexity and ambiguity of land ownership in China often frustrate restoration efforts.

Late afternoon, we visited Huishang Mansion (徽商大宅院) a short distance outside the city walls. Here a huge collection of artefacts, taken from traditional buildings that were demolished, have been assembled into a museum which displays them within the context of an elaborate reconstructed mansion. Sculptures, ponds and arches are in abundance.

We seemed to be the only ones visiting at the time and ended up staying past the closing time, wandering through the labyrinth of buildings and gardens until an irritable caretaker kicked us out.

Back in the old city, we walked through the now dark streets back to the guesthouse. For a slice of rapidly disappearing old China, Huizhou is well worth a visit. It’s too good to remain unnoticed for much longer.

Reply