As the popularity of the Shikoku pilgrimage continues to grow, many people wish to complete this journey by spending the least amount of money possible. Some try to find inexpensive or free places to stay, and others develop interesting strategies to eat cheaply, such as going to a supermarket in the evening and buying discounted fresh food products.

But if you do not stay at a pilgrim inn or hotel every night, where do you wash your body and shampoo your hair, something you cannot ignore for more than a few days? In fact, what do you do about your hair for such a long journey? Do you get a haircut or head shave beforehand, or go for a haircut midway through, or let it grow and wait to get a haircut when until you finish?

This has been a matter of concern for pilgrims since they first started making this pilgrimage several hundreds of years ago. Today, most people know the custom of giving or supporting pilgrims (osettai), but few people realize that in the past, one form of osettai was that the local people used to give free haircuts. In fact, the earliest references are from as early as the 18th century.

The illustration above is from a book printed in the early 19th century. It shows a man getting his head shaved, which could have been done as a form of tonsure indicating separation from this world or to prevent lice and other infestations that might be picked up from pilgrim lodges. Later, in 1883, a pilgrim wrote that there were people giving free meals and head shaves in a small village in present-day Matsuyama prefecture.

Another book from 1903 states that “on the porches of farmer’s one can see female pilgrims with their hair undone, while a girl or woman is kneeling down behind them to oil their hair and bind it together. On the other side, there is a barber’s room, where the men are having their haircut and their beards shaved.” (Two on a Pilgrimage. Alfred Bohner. p185)

There are two examples of women shaving their heads at temples just south of Tokushima city. One is Kōbō Daishi’s mother at Temple 18, Onzanji (恩山寺). She came here to see her son but could not climb the mountain to the temple because of the nyonin kinsei (女人禁制) system, which prohibited women on mountains. Kōbō Daishi came down to the main gate, held a goma (fire) ritual for seventeen days, and was able to break this restrictive rule. She then went up to the temple with him, had her hair cut off in a building beside the Daishi hall called “the hut of tonsure” (剃髪堂), and became a nun. There is also a stone monument in front of the building commemorating this event, but surprisingly few people know about this part of Onzanji`s history.

More famous than this story is about a woman called Okyo at Temple 19, Tatsue-ji (立江寺) in 1803. This is her story from a book, Tatsue-ji Reigenki (立江寺霊験記), written in 1925.

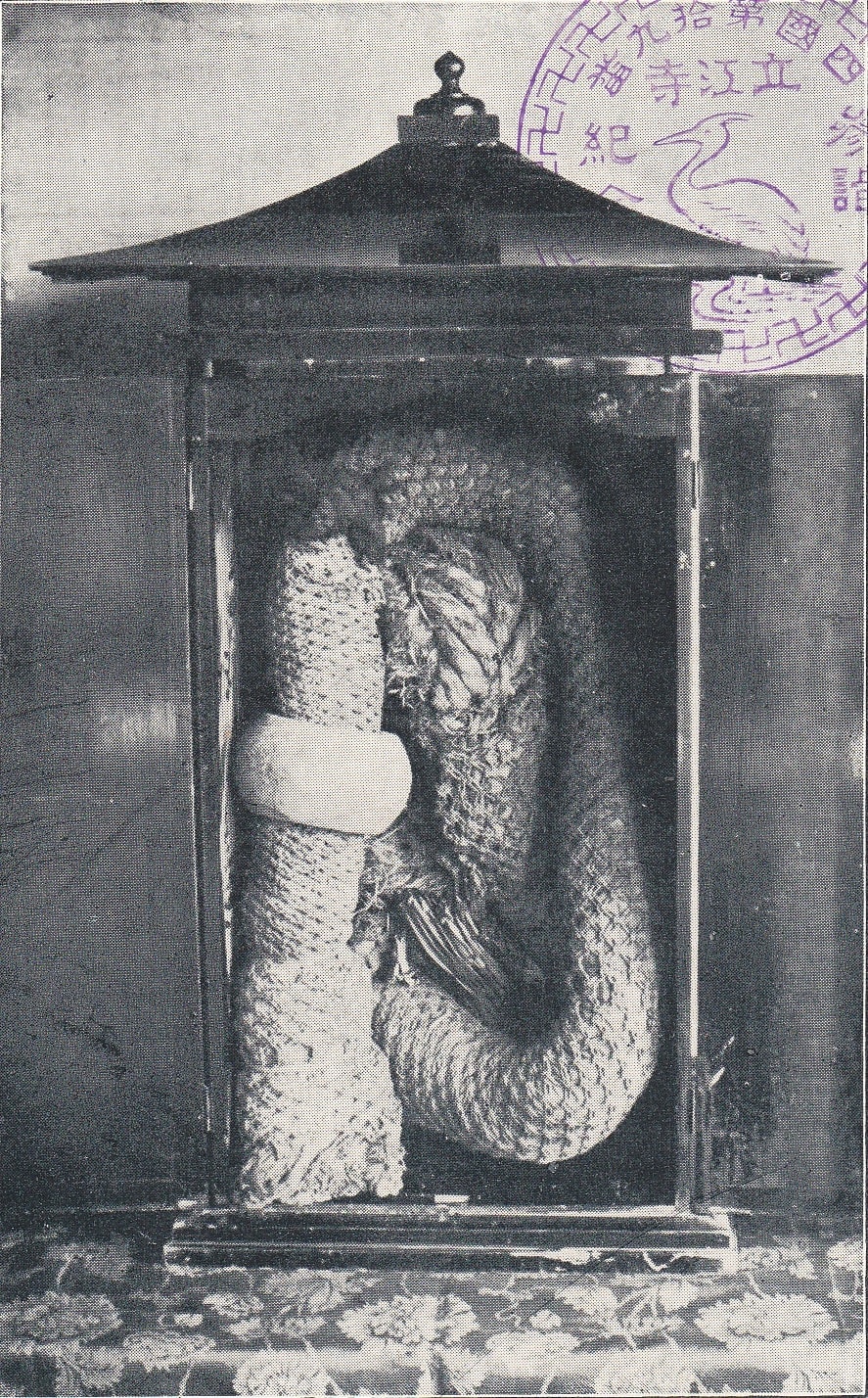

Okyō was the second of three daughters of Sakuraya Ginbei from present-day Hamada-city, Shimane prefecture. At the age of eleven, she was sold as a geisha to Hiroshima and, at sixteen, was resold to Osaka, during which time she met Yosuke and promised to marry him. At twenty-three, she ran away from Osaka, returned to her parent’s home, told her parents about Yōsuke, and married him. However, as she became ever more evil in her heart, she became increasingly arrogant. She had an affair with Chōzō that Yōsuke discovered. One day, when she tried to talk to Chōzō affectionately, Yōsuke jumped out from hiding and gave them a severe beating. Chōzō said that he did not realize that he had done anything wrong and thought to take revenge for the injuries caused by Yōsuke. Chōzō said to Okyō, “Let’s kill him.” Okyō quickly agreed and said that she would take Chōzō to Yōsuke. That night, she did so and clubbed Yōsuke to death. Under the cover of darkness, she and Chōzō crossed over the sea to Marugame, Kagawa Prefecture. They embarked on the Shikoku pilgrimage, and when they arrived at Tatsue-ji, they feared that heaven would punish them for their adultery. Suddenly, Okyō’s black hair rose up and became entwined with the bell rope. Chōzō panicked and went quickly to get the priest’s help. The priest asked the circumstances of such a sin, and when Okyō showed remorse for her actions, she was released, but her hair and scalp remained in the rope. She was lucky to be alive. Okyō had committed various grave sins, came here, and received this unexpected punishment, an act of heaven. Okyō spent time in front of the main deity statue at Tatsue-ji, repenting of her sins and returning to being a ‘real’ person. She and Chōzō lived in a small hut nearby and devotedly prayed to a statue of Jizo for the rest of their lives. Even now, the bell rope with Okyō’s hair is enshrined in the main hall of Tatsue-ji.”

When the main hall was rebuilt in 1977 after being destroyed by fire in 1974, the bell rope was placed in a concrete structure beside the Daishi hall, which is still there today.

If you are thinking of making the 1,200 km Shikoku pilgrimage by foot and plan to camp most or all of the time, maybe it would be best to shave your head before embarking on the journey to prevent any possible punishment for past sins like Okyo! Reinstating free haircuts as a form of osettai along the Shikoku pilgrimage would likely make a lot of pilgrims happy.

This article was first published in the October 2014 issue of Awa Life.

Reply