2014 marked the 100th year of foreigners observing and experiencing the increasingly popular pilgrimage. Below, I have described the key people, events, and publications related to this under-examined part of the history of the Shikoku pilgrimage.

Wenceslau de Moraes

The earliest reference to the Shikoku pilgrimage is by the Portuguese writer and naval officer Wenceslau de Moraes (1854-1929). Moraes lived in Kobe between 1898 and 1913 and in Tokushima from 1913 until his death in 1929. He was a prolific writer about life in Japan. In “Bon-Odori in Tokushima – Essays of a Portuguese hermit in Japan” there is an entry dated July 14, 1914 in which he wrote, “Something should be said with respect to the pilgrims of Tokushima, ohenrosan, the `noble pilgrims` as they are called here. It might be better to say – pilgrims of Shikoku…the pilgrim must expose himself to a thousand risks and a thousand fatigues; the greater the adventures for his devotions, the more meritous his actions become…” (p60). Unfortunately, Moraes does not mention in his writings that he experienced the pilgrimage himself.

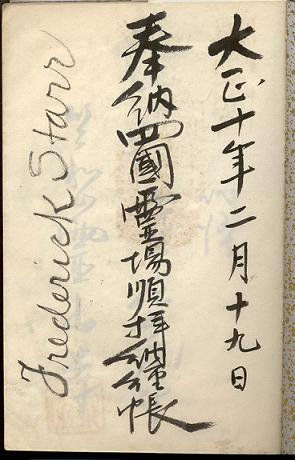

Frederick Starr

The first Westerner to embark on the Shikoku pilgrimage was Frederick Starr (1854-1933), an American anthropologist from the University of Chicago. In 1917, he completed half the route from Matsuyama to Komatsushima in about ten days, and then in 1921, made the whole pilgrimage starting and finishing from Komatsushima by foot, rickshaw and train in about thirty days.

Starr had a great interest in Kūkai/Kōbō Daishi, which was his main reason for making the pilgrimage. The other motive was to observe the compassionate customs of the Shikoku people. However, in his diaries and letters to his mother, he often complained about the risks and fatigue mentioned by Moraes. For example, “If I had really realized its length and difficulties, I doubt I would have had the courage to undertake it.” (March 27, 1921). On the other hand, Starr frequently mentioned being welcomed and treated with hospitality wherever he went.

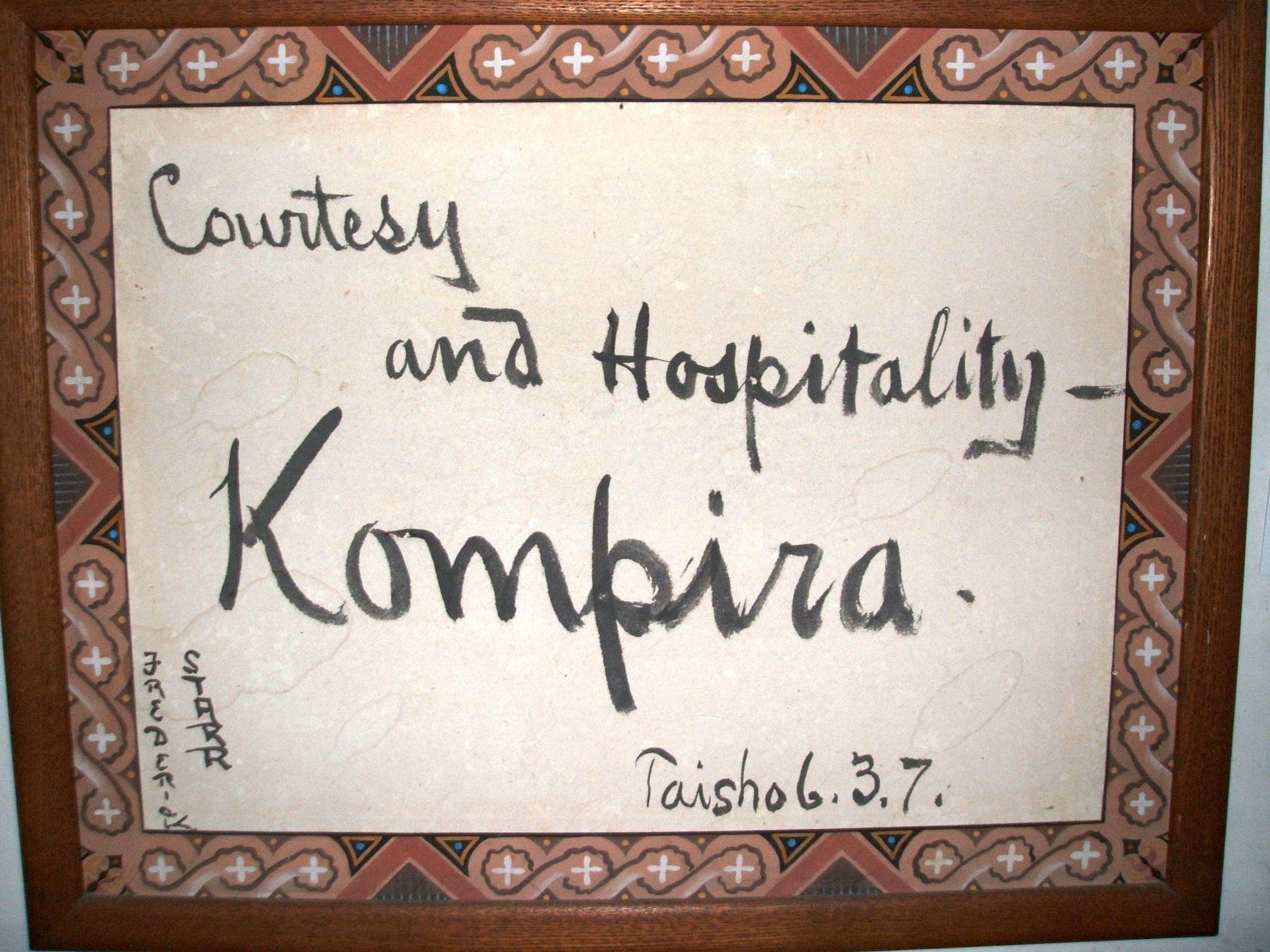

He was so impressed by his reception at Kompira Shrine in Kagawa prefecture during his first pilgrimage that he wrote “Courtesy and Hospitality” with brush and black ink on paper – now a framed memoir hanging in the shrine museum today.

At the end of his 1921 pilgrimage, he wrote a letter to all eighty-eight temples in which he expressed his gratitude for the kindness shown to him. He said that the pilgrimage around Shikoku had been one of the most interesting experiences in his life.

Prisoners of war

In July 1914, World War I broke out, and close to 5,000 Germans were captured by the Japanese during the Siege of Tsingtao in China in early November 1914. The Germans were split up and put into PoW camps around Japan, one of which was Tokushima – close to the present-day prefectural office buildings. Then when a new camp called Bandō (板東), was completed between Temple 1, Ryozen-ji and Temple 2, Gokuraku-ji in early April 1917, Germans from a few camps were moved here.

The Japanese commander was very accommodating and let the Germans interact relatively freely with the local people. In fact, in early March of 1918, an exhibition was held on the grounds of Ryozenji and at a public hall across the street from the temple. Here, the Germans displayed art objects they had made, sold food, and played music on the temple grounds. The twelve-day event was so popular that approximately 45,000 people came to visit. This is the only case when a temple along the Shikoku pilgrimage was directly involved with PoWs. In June, one German wrote a lengthy article entitled “Pilgrimage to the Eighty-eight Holy Places of Shikoku” in the camp newsletter. In it, he stated that a “real” pilgrim does not use trains, buses, rickshaws, or ships but walks the pilgrimage. Spring is also the best time to make the pilgrimage, and sentai (the custom of giving) is a tradition seen in the village along the way. (Die Baracke, June 8, 1918)

Alfred Bohner

The war ended in 1918, yet the Bando camp did not close until 1920, and some Germans even decided to stay and work in Japan. One of them was Hermann Bohner, who found work for his younger brother, Alfred Bohner (1884-1954), in Matsuyama. In 1922, Alfred came with his wife from Germany and stayed for six years. In 1927, he completed the pilgrimage and, in 1931, published an academic book about the Shikoku pilgrimage, including about ninety photographs of temples and pilgrims. Like Starr, Bohner received many gifts and kindness from the local people, but sometimes it led to humorous situations. For example, he wrote that as a German, he was repeatedly given beer at breakfast because it was written in junior high school textbooks that beer replaced tea in Germany. But he is greatly surprised by the degree to which this selfless custom of giving is carried out and said that it is something not dreamed of in modern cities, even in Japan. Copies of Alfred’s original book are very hard to find. Still, in recent years, the publisher has republished the German edition and an English translation, which was done by an American friend of Alfred’s in 1941.

For the next forty years until the late 1960s, there are no references to non-Japanese coming to make the Shikoku pilgrimage, nor are there any publications about their experiences. Only a few short descriptions of certain temples along the pilgrimage route are in guidebooks made for foreign tourists. For example, in 1936 and 1947, the Japanese Tourist Bureau published a small booklet in English titled “How to See Shikoku”, on which they put a pilgrim on the cover and stated that “Shikoku has been a land of pilgrims and the 88 temples of [Kōbō] Daishi are still preserved.” Unfortunately, the history of foreigners and the Shikoku pilgrimage does not resume until Oliver Statler comes to Matsuyama in 1968.

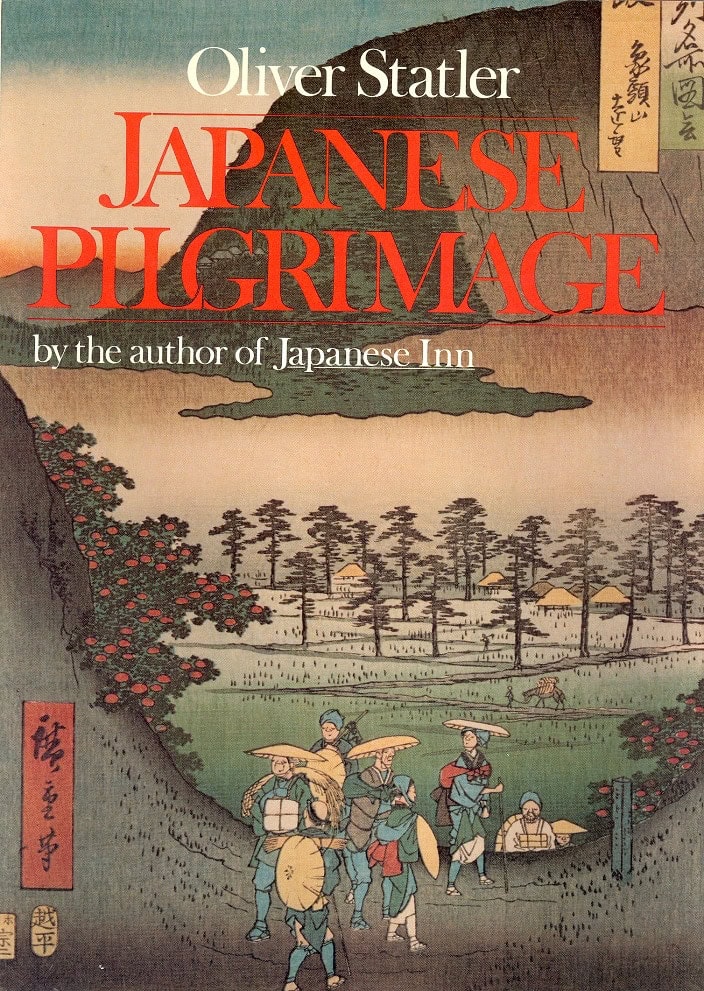

Oliver Statler

Oliver Statler (1915-2002), a researcher of Japan from the University of Hawaii, was very influential in promoting the Shikoku pilgrimage to the West. During WWII, he worked as military personnel in the Philippines and New Guinea and between 1947 and 1954 worked in Tokyo and Yokohama. Later, while staying in Shimoda city (Shizuoka prefecture) from 1960 to 1961, he visited Shikoku for the first time and thought he would like to write about the pilgrimage someday.

In 1968, he returned to Japan and stayed in Matsuyama City for three years. During this time, he made the pilgrimage several times on his own, but then, during the 1970s and 1980s, he often led “pilgrimage tours” for groups of students from Hawaii and Kyoto. In one article he wrote, “The Shikoku pilgrimage draws on the roots of Japanese culture and the study of it cannot help but illuminate that culture” but also stressed that “the temples punctuate the pilgrimage, they do not constitute it” (Matsuyama Univ. of Commerce Review, 1975). He also strongly felt that “going around in a bus or a car may be meritorious, but it is not ascetic exercise and it is not performing the pilgrimage” (letter written by Statler, 1979).

In 1983, Statler published a book, Japanese Pilgrimage, in which he intertwined stories from the history of the pilgrimage and his own experiences as a pilgrim. However, unlike Bohner’s book, Japanese Pilgrimage was distributed throughout the West and, as a result, allowed people to learn about this historically and culturally rich journey in English.

Some Japanese people also published books in English, which helped to promote the Shikoku pilgrimage. For example, Mayumi Banzai wrote A Pilgrimage to the 88 Temples in Shikoku, Japan, based on her pilgrimages around the island in 1971 and 1972. In the Preface, she wrote that she wants “to explain as much as I can to foreign visitors in the hope that they will agree with my conclusion that Kobo Daishi was the purest and most hardworking priest who ever lived in Japan” (Banzai, p10).

Recent publications

Another and perhaps more widely known book was A Henro Pilgrimage Guide to the 88 Temples of Shikoku Island, Japan, published by Bishop Taisen Miyata in the United States in 1984. After graduating from Koyasan University, Miyata went to the US and, in 1959, took over the Koyasan Betsuin Temple in Los Angeles. He made the Shikoku pilgrimage seven times between 1955 and 1992, and in 2014, at the age of 82, he guided a group from California on his last “pilgrimage tour.” In his book, which has gone through four editions (the latest in 2006), he explains how to make the pilgrimage and describes the history of each temple and the major deities seen at the temples. Miyata knew about Statler and wrote, “I am thankful for his work and effort to introduce the Shikoku henro to the Westerners” (Miyata, 157). Unfortunately, unlike Statler’s book, both books are almost impossible to obtain nowadays.

From the 1970s onwards, other people from around the world who embarked on the Shikoku pilgrimage have written articles or books about their experiences. Various documentaries have also been made, and descriptions have been included in guidebooks for Japan. For example, the 2005 Lonely Planet recommends that “If you have time and the inclination the best way to see and experience Shikoku is to journey around the 88 Sacred Temples. Shikoku is a very special place, but a lot of people rush through and leave without really understanding what it has to offer” (p569).

However, until the widespread use of online information on the pilgrimage, it could be difficult to acquire. In 1999, David Turkington from the US used this new form of communication to share his pilgrim experience in almost real-time by uploading his diary every few days onto his website via public phones. Actually, it was Statler`s book that he found at a bookstore in Tokyo in the 1980s that triggered his curiosity about the pilgrimage so much that after reading the book, he knew that someday he would travel to Shikoku and walk the pilgrimage. Turkington’s website provides lots of practical information regarding the Shikoku pilgrimage and includes a forum where people can post questions and answers about the journey.

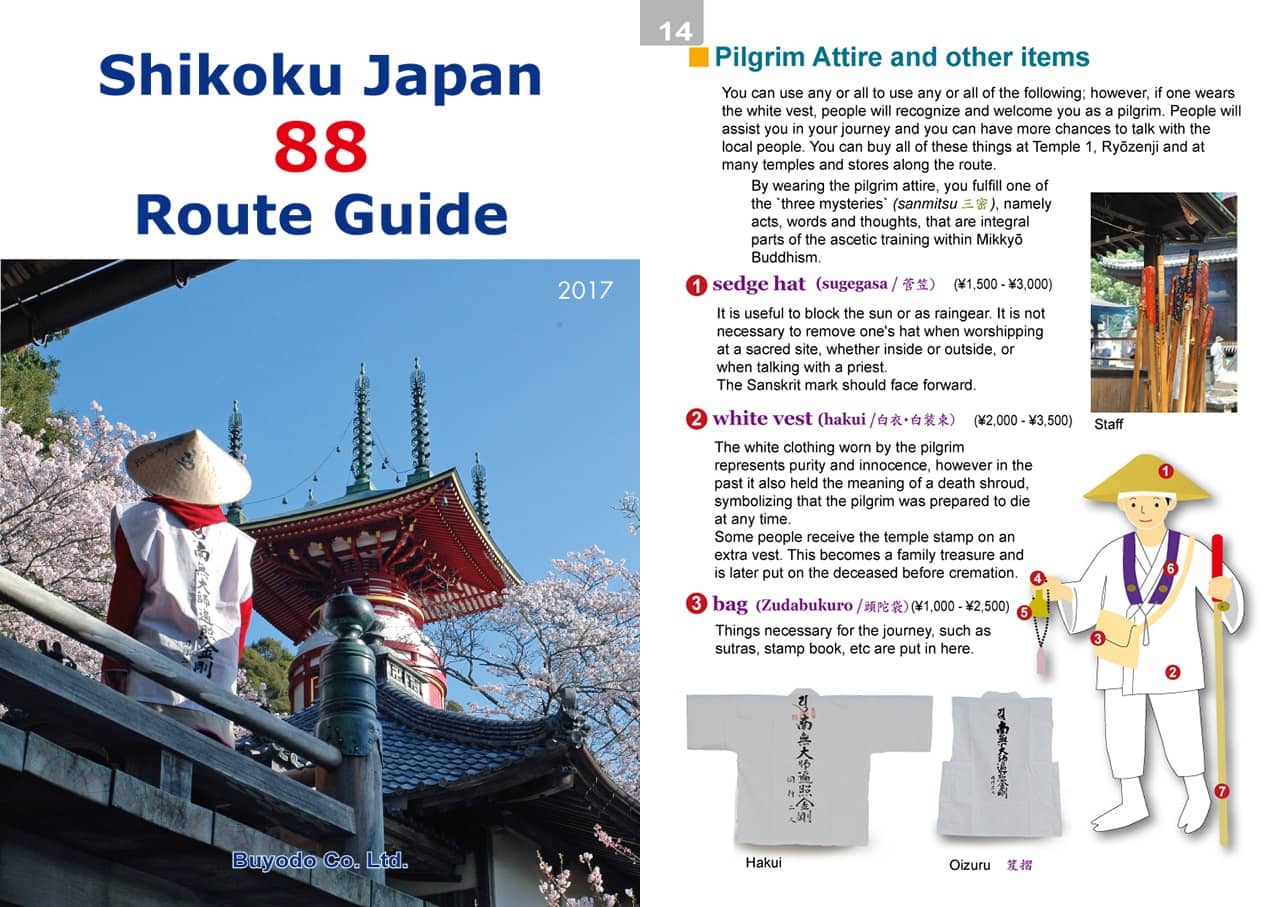

Yet, with even more material in printed form and explanations and descriptions on the Internet, foreigners still had problems getting around because there was no guidebook in English until 2007. However, with the publication of the Shikoku Japan 88 Route Guide, people could now read the maps for the route without knowing any Japanese. In fact, the popularity of the book has been so great that more than 7,000 copies have been sold!

No one can deny that the number of foreigners making the Shikoku pilgrimage is growing due to a dramatic surge in information on the Internet and exposure via the mass media. Yet, what will the future be like regarding this part of the pilgrimage? People like Starr, Bohner and Statler and many others in the past have greatly enjoyed this pilgrimage, so perhaps during 2015 get out and experience it for yourself, and then help to preserve it for people from around the world to enjoy in the future.

This article was first published in the December 2015 & January 2016 issues of Awa Life.

Reply