Our first visit to Naoshima in 2023 was one of the most enjoyable trips we had made post-COVID, and I left determined that we must return to fill in the gaps of all the places we ran out of time to visit back then.

Naoshima (直島) is a place of profound beauty that could only exist in Japan because it embodies a unique blend of cultural values, historical context, and aesthetic sensibilities deeply rooted in Japanese philosophy and society.

Art isn’t confined to museums here; instead, the museums feel like they’ve grown out of the land, effortlessly integrating with the island’s landscape.

Part of its magic lies in its remoteness—Naoshima isn’t easy to get to, but that only deepens the sense of discovery. It’s an experience that lingers long after you leave, which is why it was top of my list of places I wanted to visit on our first trip back to Japan.

After renting bicycles and riding to the Honmura district, we visited Minamidera, a monolithic, windowless structure designed by Tadao Ando to house James Turrell’s Backside of the Moon.

Stepping inside, you are enveloped in complete darkness. With no visual anchors, your eyes must gradually adjust until a subtle, almost imperceptible glow emerges from an unseen source, challenging how we perceive light, space, and reality.

Unlike many of Turrell’s other works, which immerse viewers in vibrant color fields, this installation begins with an absence of light, pushing perception to its limits. It embodies the essence of ma (間)—the Japanese concept of negative space—creating a meditative experience that heightens awareness of the act of seeing itself.

Stepping back into daylight after the complete darkness of Backside of the Moon felt almost disorienting. This heightened awareness carried over to our next stop, the Ando Museum which occupies a traditional Japanese wooden residence.

From the outside, it blends seamlessly with the village, but inside, Ando’s signature exposed concrete is woven into the structure, creating a quiet dialogue between past and present.

The museum showcases models, sketches, and photographs of his architectural projects, while a small underground cylindrical void, illuminated by a glass aperture, introduces an element of mystery.

Walking up the hill, we returned to Go’o Shrine, a historic Shinto site reimagined by Hiroshi Sugimoto. His addition of an optical glass staircase descending into an unseen world below transforms the shrine into something both tangible and transcendent.

Both Ando and Sugimoto manipulate light to heighten awareness. In the Ando Museum, light and concrete create a meditative stillness, emphasizing spatial tension. At Go’o Shrine, light filtering into the underground chamber suggests a passage between worlds, much like the way ancient shrines connect the human and divine.

These spaces are more than architectural interventions—they are portals to deeper contemplation. The Ando Museum reframes history through architecture, while Go’o Shrine meditates on the boundary between the physical and spiritual. Both remind us that what is unseen often holds the greatest significance.

For me, these hidden spaces echoed Haruki Murakami’s metaphysical thresholds and subterranean realms—places that serve as gateways to deeper layers of reality and the psyche, waiting to be discovered by those willing to look.

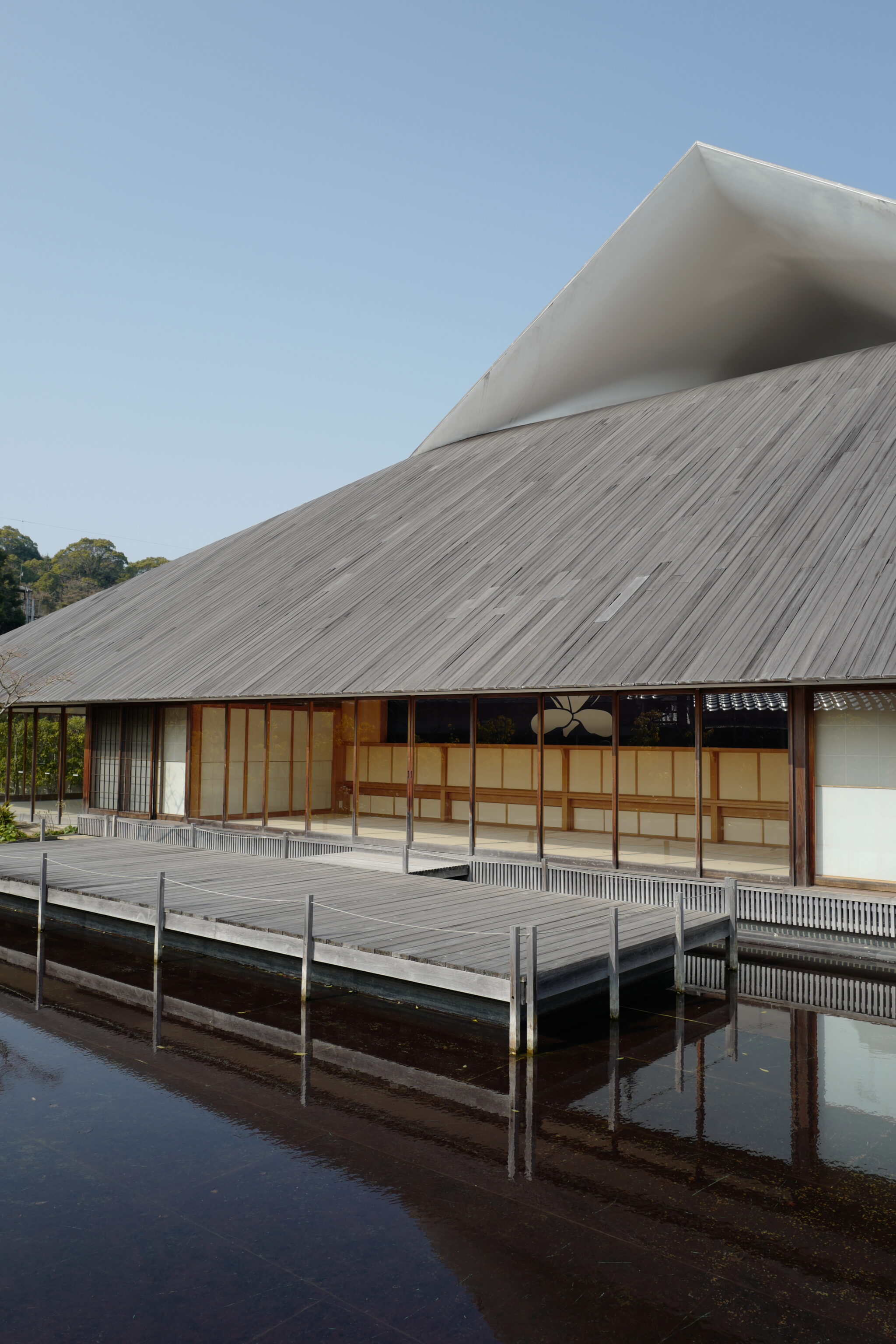

Also in Honmura, Hiroshi Sambuichi designed Naoshima Hall as a community center and sports hall to help revitalise the island. The building’s hinoki wood roof, which has turned a beautiful silvery grey, resembles traditional architecture, while its design allows for natural ventilation and ambient light.

Originally the home of a wealthy salt merchant, the Ishibashi House dates back to the Edo period. Carefully renovated to preserve its traditional architecture, the house has been transformed into an art space featuring works by contemporary artist Hiroshi Senju, renowned for his serene waterfall paintings.

For this space, Senju created a massive, wall-spanning waterfall painting using natural mineral pigments on traditional Japanese washi paper—a hallmark of nihonga (Japanese-style painting). Its monochrome palette and flowing lines evoke cascading water, enveloping the viewer in a tranquil, immersive atmosphere.

Senju prefers his paintings to be viewed under natural light, allowing the waterfall to appear almost as if it’s moving. One of the attendants mentioned that the pigments are subtly changing over the years, making the artwork feel as though it is evolving—just like a real waterfall.

After lunch we rode our bicycles to the south side of the island and arrived just in time for our timed tickets to the Hiroshi Sugimoto Gallery: Time Corridors.

The concept of “Time Corridors” reflects Sugimoto’s lifelong engagement with the passage of time, capturing moments that feel both ancient and timeless. His works often explore long exposures, blurred boundaries between past and present, and the interplay between light and shadow.

The gallery, also designed by Tadao Ando, serves as a bridge between Sugimoto’s earlier endeavors on Naoshima and his later creations, notably the Enoura Observatory in Odawara (one of my favourite places in Japan).

The way Ando’s minimalistic architecture interacts with light, shadows, and space makes even the simplest moments—walking through a concrete hallway or looking at a sculpture through a perfectly framed window—feel intentional and poetic.

A highlight of the gallery is the Glass Tea House Mondrian, a sleek, transparent box composed entirely of glass, with the exterior designed to dissolve the boundaries between the interior and the surrounding environment.

The design is influenced by Piet Mondrian, the Dutch modernist painter known for his grid-based compositions using primary colors and black lines. Sugimoto merges Mondrian’s minimalist aesthetic with the principles of Japanese tea ceremony, creating a fusion of Western modernism and Eastern tradition.

The tea house’s minimalist design, with its clean, sharp lines and geometric forms, contrasts sharply with the organic, natural surroundings of Naoshima. This approach challenges the traditional notion of a tea house as an enclosed, intimate space, inviting the natural world to become a part of the experience.

This fluidity of boundaries is also a nod to the concept of “wabi-sabi,” which celebrates beauty in imperfection and the passage of time.

After enjoying the works, we sat down for a beautifully presented cup of tea in the lounge while admiring the view. It’s a serene, contemplative space, designed to complement the minimalist ethos of the gallery.

Our final stop of the day was the Chichu Art Museum (地中美術館) which I wrote about in my 2023 post. Whilst it might not have had quite the same impact as our first visit, the works by James Turrell, Walter De Maria, and Claude Monet are still spectacular within the context of the subterranean yet naturally lit building by Tadao Ando.

Cycling back along the coast to Miyanoura ferry port, we were treated to a breathtaking sunset. I couldn’t have imagined a much more enjoyable day.

Beyond the spectacular art, architecture, and nature, another aspect that makes Naoshima so special is that it’s not crowded, offering a more personal and unhurried experience with the artworks without the distractions of larger, more commercialized museums.

With the opening of the Naoshima New Museum of Art in May 2025, I now have one more reason to return!

Reply